Wine Enthusiast |

| Can Sweet Wine’s U.S. Image Be Rehabilitated? Posted: 02 Aug 2021 04:30 AM PDT  "It's not sweet, right?" Sommeliers are asked the question at least once a day, says Zaitouna Kusto, general manager and sommelier at Esters Wine Shop & Bar in Santa Monica, California. "These well-meaning people aren't wrong about their tastes, of course, but they are potentially misguided by a number of sociological factors they may not even realize." American sweet wines have long had a poor reputation. In stark contrast to the grand sweet wine traditions of Europe, like Sauternes, Tokaji and Italian passito, U.S. bottlings are often lumped together with poorly made, sugar-laden sweet offerings sipped by those thought not to know "real wine." "Over the years, the perception [of sweet wine] in the United States was not the best…a lot of people associated it with unsophisticated wine," says Pauline Lhote, winemaker at Chandon in Napa Valley. "But there are so many examples, whether in Europe or the U.S., showing that's not the case at all." A new crop of winemakers, particularly in previously overlooked areas like the Midwest, are earning appreciation and reversing negative stereotypes with high-quality, easy-drinking sweet wines that deserve a spot on your table.  How Sweet Wine Is ChangingThe numbers tell a big part of this comeback story. Sweet wine is now a $1 billion industry in the U.S., according to Nielsen. It makes up about 13% of total wine sales and grew 8% in 2019. The pandemic spurred an increase of more than 22% in overall wine sales, and sweet wine sales rose a whopping 40.1%, according to data from NielsenIQ and IRI's National Consumer Panel. Sweet wines can often be an entry point for new wine drinkers. One in three new wine consumers start with these bottlings, according to the National Consumer Panel. But that doesn't mean more experienced wine lovers should shun sweet. "The biggest misperception I've seen is dismissing wines that have sweetness as not being a quality wine," says Dennis Dunham, director of winemaking at Oliver Winery & Vineyards in Bloomington, Indiana. He says that sweetness is just another attribute of wine, like acidity, tannins or body.  "There's a notion in the industry that folks ought to progress from sweet to dry," says Dunham. "We think you should drink what you enjoy." One reason for sweet wine's bad rap has to do with how they were often made. "Sweetness is a kind of cloaking, and no serious wine person will deny that it has historically been used to disguise unqualified dry wine," says Scott Carney, master sommelier and dean of wine studies at Institute of Culinary Education in New York City. He says it requires real skill to make high-quality sweet wine. What Makes Good Sweet WineA good sweet wine, like all good wines, starts in the vineyard with quality grapes. "It's like cooking, the ingredients are very important," says Lhote. Palmaz Vineyards in Napa Valley has made sweet wines since 2003. At first, the producer sourced Muscat grapes for its Florencia Muscat from independent growers, but started to raise its own in 2009. "It's not that Muscat grapes were necessarily hard to grow, they just weren't in high demand," says Tina Mitchell, Palmaz winemaker. Transitioning to estate-grown grapes for Muscat enabled Palmaz to have greater control over sweetness. It also allowed them to harvest when fruit had the desired flavors, in their case, orange blossom, mango and papaya. That move, combined with a stylistic change made five years ago that reduced the wine's residual sugar and increased acidity, has made Florencia the best it's ever been, says Mitchell.  "Most people who come to a winery aren't looking for a dessert wine, and we surprise them with it [in the tasting room]," she says. Some winemakers aim for a sweet wine to create tension in the palate. "You need to have a balance between acidity and sweetness," says Lhote. "If you don't, the wine will be very cloying." She cites the second-glass effect, and always asks her team at Chandon: Would you drink more than one glass of this? Would you drink the whole bottle? If the answer is no, the wine needs more work. High-quality sweet wines should have the perception of sweetness without being syrupy, while remaining creamy and smooth. "The key is finishing on a dry note," says Lhote.  Why Sweet Wines Are TrendingA major reason that high-quality sweet wines have seen a resurgence is because they pair so well with food. "Sweet wine adds variety and depth to any wine list and can be a great tool for pairing with dishes beyond dessert, like salty and spicy food, because of the natural acidity," says Megan Mina, beverage director at Zero Restaurant + Bar in Charleston, South Carolina. Juan Cortés, beverage manager at The Chastain bistro in Atlanta, says few things can elevate a dinner like properly made sweet wine, which can age well and transform over the years. Two of his favorites are Philip Togni's Ca' Togni, a sweet red made from black muscat grapes grown in Napa Valley, and Martinelli's Muscat of Alexandria, from Jackass Hill vineyard in the Russian River Valley. "I would put [Martinelli's] side-by-side with the finest European sweet wines any day," says Cortés.  People often associate sweet wines with dessert for good reason. Alongside dessert, the wine often doesn't taste as sweet, says Caroline Conner, wine coach and founder of Wine Dine Caroline. But sweeter wines pair well with much more. Conner points to racy, off-dry styles of Riesling or Pinot Gris that can help alleviate spiciness of Thai cuisine, or how rich Sauternes meets its match in deeply savory, salty foie gras. Mina agrees. "For those who don't like the idea of 'sweet' wine, I let them know this is not their mother's Riesling," she says. They also make great cocktail ingredients. Take Oliver Winery's Lemon Moscato, which debuted earlier this year and sold out of its initial bottling run in only a few weeks. With a bit of fizz from fermentation and 6.8% alcohol by volume (abv), the wine has a lightness that lends itself to being served over ice. It can also be combined with a splash of elderflower liqueur and topped with dry Champagne to make a refreshing spritzer. It can still be tough to get consumers to buy a bottle of wine labeled "sweet." That's why many discover a true appreciation for sweet wine in a tasting room. According to Lhote, "Once you have people try it, they really love it." |

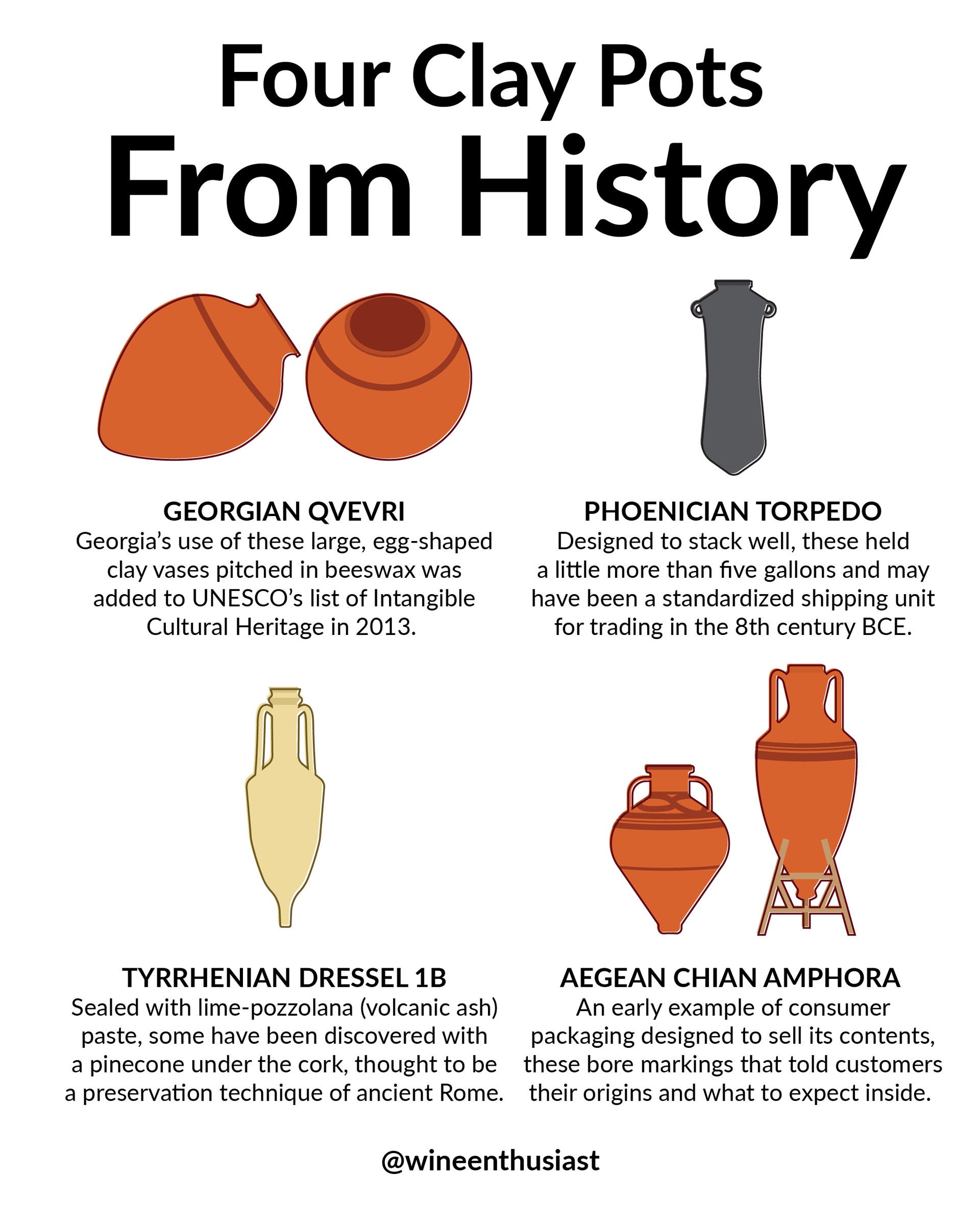

| More Than Amphorae: The Ancient World’s Other Answers to Aging Wine Posted: 02 Aug 2021 04:00 AM PDT  Increasingly adapted by modern-day wine producers, the age-old practice of vinification using clay containers is becoming more recognized by today's beverage lovers. Yet, "amphora" remains misused as a blanket term to refer to any clay vessel used to ferment and age wine. From the Greek word amphiphoreus for "something which can be carried from both sides," amphorae are oblong, two-handled vases with fat bodies, pointed ends and narrow necks, a 15th-century BCE invention of the Canaanites who inhabited the Syrian Lebanese coast. They were crafted from clay not for vinous reasons, but because it was an abundant natural resource. The vessels were easy to produce, ship and reuse. Utilitarian, their bulbous shape provided maximum storage space, tapered ends allowed for rolling and slender necks helped manage pouring. With interiors pitched in pine resin to render them waterproof, amphorae were used to hold wine, but were also packed with goods like oil, grains and nuts. Sealed with a plaster stopper, they would be layered in the hull of a ship, sent across the seas and exchanged widely throughout the Mediterranean Basin. The use of clay jars for wine production in particular can be traced to 6000 BCE Georgia. Massive stationary vessels called qvevri, some more than 250 times the size of amphorae, were kept cool underground. Here, clay was used to the wine's benefit. Granularly speaking, clay is inert and porous, which allows for steady temperature regulation and microoxygenation without absorbing flavors, aromas or tannins like other materials like oak. Utilized throughout the entirety of production, intact containers were reused indefinitely.  |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Wine Enthusiast. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment