Wine Enthusiast |

- ‘It Has to Be Vibrant’: The Evolving Rosés of Provence

- Rise to the Occasion: Making Yeast Cultivation a Career

- What Does ‘Minerality’ Mean in Wine?

| ‘It Has to Be Vibrant’: The Evolving Rosés of Provence Posted: 18 May 2021 04:59 AM PDT  A bottle of Provence rosé can evoke similar feelings to a beautiful sunset. Its color and luminous bottle precipitate enjoyment. The pleasure begins before the bottle is even opened. That pale rosé color, the vibrancy and freshness that shine from the glass: This is Provence. Even in the depths of winter, the wines sing of sun, blue sky and dining on the patio. Stephen Cronk, owner and CEO of Mirabeau Wine in Cotignac, calls the color "paramount. It has to be vibrant." Shade is so important, in fact, that wineries test it. "Since 2018, we have been using analytical measurements on the color of rosé wines (chromametry), allowing us to be more precise on the different colors and their evolution," says Olivier Ravoire, director general of Famille Ravoire wines, a négociant based in Salon de Provence. The pale color at the heart of Provence rosé comes from the fact that Grenache, the mainstay of so many wines, has a relatively pale skin. Cinsault, its partner, is equally prone to a light color. It's only when Syrah or Cabernet Sauvignon are added to the blend that color becomes an important element, and something a winery needs to control. There was a time, in the 2017 and 2018 vintages, when the pale color of Provence rosé became almost white in some wines. If you held a glass up to the light, it was hard to tell. Only the wine's aromatic fruitiness and texture gave the game away. That tendency has, happily, gone in the 2019 and 2020 vintages. The 2020 vintage marks a return to color. We look at the past, present and future of this magnificent style. Setting the Benchmark for RoséProvence has become the international standard by which other rosés are judged. The flavors from the blend of Grenache and Cinsault, spiced by Syrah, Mourvèdre and Tibouren, and freshened by white grapes like Vermentino, are what rosé drinkers seek. A Provence rosé is lightly spicy, with intense red fruits, citrus and sometimes a touch of minerality. There's always fresh acidity, a crisp touch that makes the wine refreshing and moreish. Ravoire outlines the steps that go into how to create a rosé with the right color and flavor profile. It's complicated. "We harvest at night to prevent any oxidation of the juices and to keep the grapes cool," he says. "Then we soak them at a low temperature. That allows us to control the color, keeping the wine pale while allowing the flavors to develop." The grapes are pressed gently, he says, and only the juice that has just the right color is used.  A Taste of Past and PresentProvence, in the South of France, has a long wine history. Vines were planted from 600 B.C. by the Phoenicians who founded the city of Marseilles, and then cultivated by the Greeks who colonized the region. The Romans ran the region from the second century B.C. and gave it its name: Provincia, the province, their first colony outside the Italian peninsula. Given this long history, it's delicious irony that today's signature Provence wine should be so modern, a wine that relies on technique in the winery as much as it does on those ancient vineyards. While rosé production is more about technique than romance, remember that the grapes here come from vineyards that increasingly prioritize organic farming and preserving biodiversity. The aim is to be 100% organic by 2030, according to the Provence Wine Board, the industry's trade body. That creates a dichotomy: vineyards that preserve nature alongside wineries that are seriously high-tech. It's a world away from the dusty cellar full of barrels. Not that barrels have been dismissed from the world of Provence rosé. Some rosés become complex and matured in barrels. This has created a series of profiles, from simple, quaffable wines to those that are rich, full-bodied and worth aging. They have prices to match, from less than $20 to $100. The vineyards and estates of Provence lie in a landscape full of drama and light. Mountains are all around, like Mont Saint-Victoire, Massif de la Sainte-Baume, Massif des Maures and Massif des Alpilles surmounted by the hilltop fortress of Les Baux de Provence. Lavender fields are everywhere. The town of Grasse supplies many of the major Paris perfume blenders. Towns, especially away from the coast, are unspoiled, many situated in defensive positions on hilltops, while the must-visit college city of Aix-en-Provence is at the heart of one of the Provençal appellations. Wine estates have created restaurants, luxury hotels, exhibition centers and open-air theaters. Ready for its Close-UpIt's little wonder that Provence has attracted entertainment stars to enjoy its lifestyle and beautiful landscapes. It's created a new category—the celebrity rosé. Names include Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie of Château Miraval; Star Wars Director George Lucas at Château Margüi; rapper Post Malone with Maison No 9; and Sarah Jessica Parker with Invivo X. These celebrity-name bottlings have been followed by those of heavy hitters within the industry. The biggest of all is Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy (LVMH), owner of Champagne houses, Cognac producers and Bordeaux chateaus. Last year, it took control of the most famous name in Provence rosé, Château d'Esclans, which produces Whispering Angel and the $100-a-bottle Garrus. Americans have fallen in love with Provence and its rosés. The U.S. is the top foreign market for Provence, with a whopping 46% of exports by volume in 2019. Gone are the days when rosé (called blush) was mainly sweet. Rémy Devictor, owner of Domaine de la Sanglière in Bormes les Mimosas, describes rosé as "having the joie de vivre, the enjoyment of life, that we have in Provence. People are looking for joy, lightness, freedom, and that's what we supply. And, besides, it is beautiful to drink." If all this seems a far cry from the jug of rosé in a Provençal café or bar, consider that Saint-Tropez and Cannes are also in Provence. Luxury has been a part of the mix there for at least two centuries. As much as the color, bottle and taste, that sense of luxury is part of the allure of Provence rosé. It brings that whiff of lifestyle as well as fruity aromas. No longer a one-size-fits-all shade of pale, it allows wine lovers of all stripes to sip with the famous from the comfort of home. Any time we yearn for escape, a bottle of Provence rosé should be at hand. The AppellationsCôtes de Provence. This is the heart of Provence rosé. Aromatic, fruity, floral and sometimes with a light herbal character, the wines are mostly enjoyed young, which keeps the freshness and bright immediate appeal. There are two cru vineyards: Mont Sainte-Victoire and La Londe. Their wines have extra richness and a higher price. Coteaux d'Aix-en-Provence. Centered on the city of Aix-en-Provence, these rosés are full-bodied and often bolstered by Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah, which give structure. That means they can age, although they can also be enjoyed in their youth. Coteaux Varois en Provence. Between the Côtes and Aix, Coteaux Varois en Provence is beginning to show real quality. Similar in many ways to the two larger appellations, the best wines seem to have more of a crisp character, more bounce and vibrancy. Les Baux de Provence. The farthest west of the Provence appellations, it's the only one that's entirely organic, with many biodynamic producers. Rosés are full-bodied, and sometimes hint at nuttiness as well as a mineral texture. Bandol. From vineyards with a maritime influence and distinguished by the prevalence of Mourvèdre in the blend, the rosés are spicy, rich and aromatic. Of all the Provence rosés, these age the best. |

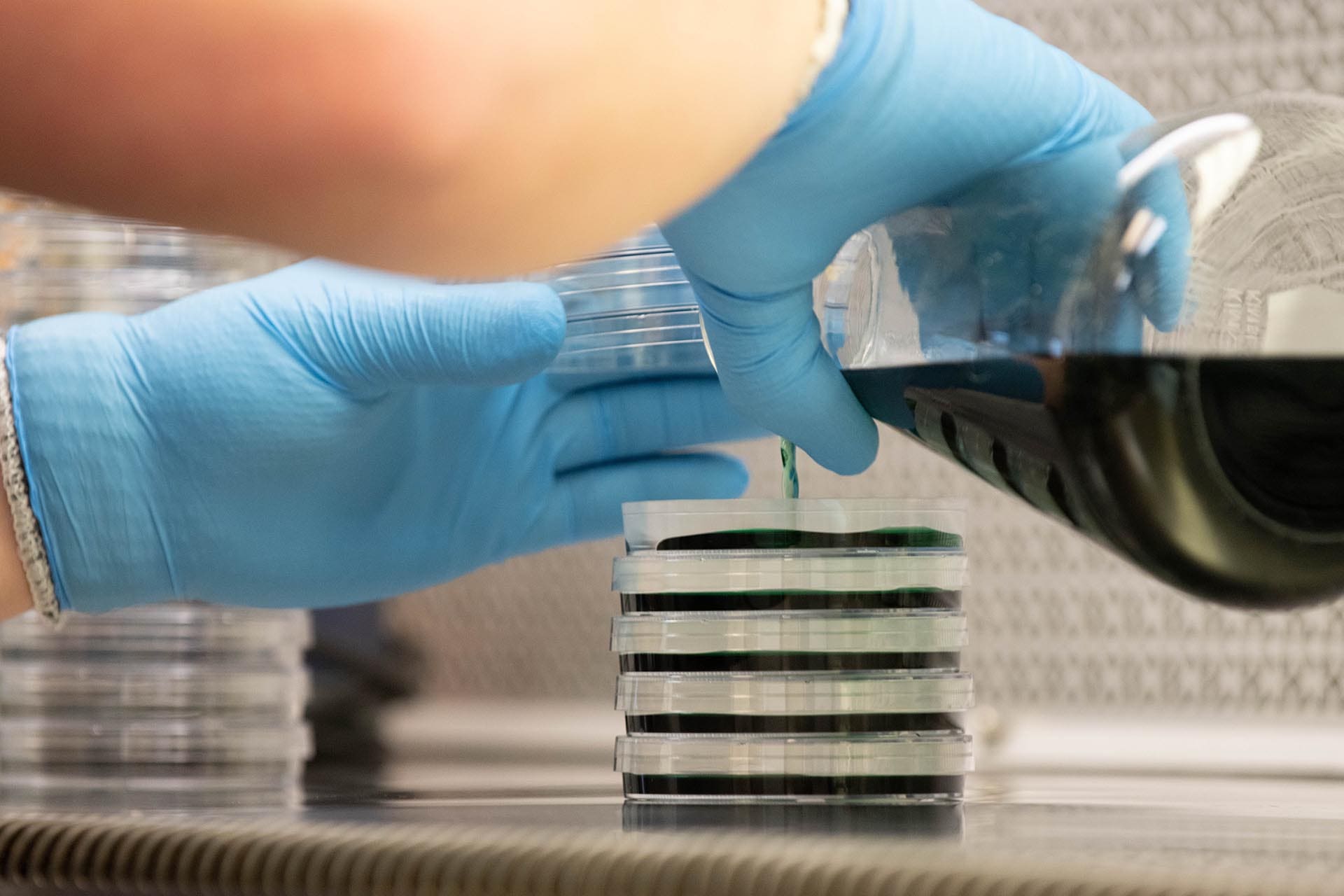

| Rise to the Occasion: Making Yeast Cultivation a Career Posted: 18 May 2021 04:30 AM PDT  Yeast is essential for fermentation, the critical process that converts grape juice into wine. Although most grapes have enough natural yeast on their skins to start a reaction, relying only on spontaneous fermentation is risky (though some producers do exactly that). What if there isn't enough yeast to finish? What if it takes too long, or it leaves sugar that can be consumed by bacteria that cause spoilage? Winemakers unwilling to shoulder those perils typically add pure yeast cultures to their fermenters. This makes fermentations more reliable and helps deliver more consistent wine sensory profiles.  These cultures come from a yeast cultivator, whose job—as it sounds—is to propagate, grow and manage pure yeast. These companies either dry yeast cultures or bottle them fresh and sell them to winemakers, brewers, saké makers, kombucha enthusiasts and more. The job is part science, part art and all important to the industry. Getting the right yeast is critical because these microbes are more than just the engines of fermentation. Different yeasts produce different outcomes.  "With bread, you're looking for yeast to produce gas to make the bread rise," says Didier Theodore, new business development and yeast product manager for Lallemand Brewing, which has produced yeast cultures since the 1970s. Theodore works alongside Anthony Silvano, yeast product manager at Lallemand Brewing in oenology. "For wine, you are looking for yeast to consume sugar and produce alcohol and aroma. It's completely different,” says Theodore. Given that aroma matters at least as much to wine as flavor, finding the right yeast is vital and tricky. A yeast strain that produces ideal results with one grape variety will not necessarily work as well with others.  "For Sauvignon Blanc, you want to ferment it to preserve the fresh aromas," says Theodore. Someone who makes Chardonnay, on the other hand, may want to emphasize creamy or yeasty flavors. "We will test the yeast in different conditions in the lab," he says. "Then, after fermentation, we will taste the wine and make some analyses of the wine to see which kind of aromas have been produced during fermentation." In addition to identify and capture strains that will offer something new or different, yeast cultivators also work closely with beverage producers to help solve problems.  "We serve as a source of technical information for the fermentation industry," says Dr. Matthew Winans, a research and development scientist at Imperial Yeast, founded in 2014. "We do that by working with customers to troubleshoot problems they're having and leveraging lab resources to solve problems." Whether it's a tried-and-true yeast or a new one, cultivation typically starts in the lab with a single yeast cell. "We isolate it, propagate it, and it grows," says Winans. "Once the lab achieves growth to a sizable quantity, we move it over to the production facility."

The production team inoculates the yeast into a sterile slurry called bulk media, which is where the yeast grows. The yeasts reproduce until there's a sizable quantity to sell. For technicians in both the lab and production, much of the job is to monitor the yeast cultures to ensure they're healthy and pure, and to clean the facility so that bad microorganisms don't contaminate the final products, says Winans.  At Imperial Yeast, the team uses a thermal cycler that monitors real-time polymerase chain reactions by detecting fluorescence in samples and allowing lab techs to copy DNA from yeast in the bulk media and test it to see if it has contaminants. A fluorescence-imaging machine allows them to count cell density from an image to package consistent concentrations of yeast cells. One of Theodore's favorite parts of the job is working in the field. "It's fun because the brewing industry and the wine industry are very social," he says. "They're an international element to the work because we are selling our products all over the world. We are also making a product to make people happy." Working for a yeast cultivator isn't all about discovery and drinking, though. There's some bias toward the profession, especially in Europe.  "When you start to speak about yeast, people think that you are putting something strange into the grape juice, and this is not something that's natural," says Theodore. It's challenging to explain to people that you're taking the best from nature and using it to craft a natural product. There are other unglamorous aspects to the career. Anyone who interacts with the yeast must clean or sanitize workspaces and equipment, and that's not for everyone, Winans says . The job also requires a person who is highly organized, has great attention to detail, can communicate well with other team members and is very thorough. Someone who appreciates this type of work but doesn't have an advanced degree in microbiology can still have a good career in yeast cultivation. "An interest in microbiology and fermentation helps," says Winans. "We can teach or train just about any employee on anything they want to know, but we can only do that if someone has a desire to learn and an interest in this field." Flexibility, an ability to work with a team and a willingness to put in long days when necessary are other qualities he looks for.  To work in R&D or more advanced positions in a lab, "you need to have a good knowledge of microbiology and different microorganisms—which are good, which are bad," says Theodore. People who can rise to the occasion and work in yeast cultivation will find it an interesting, fulfilling career. |

| What Does ‘Minerality’ Mean in Wine? Posted: 18 May 2021 04:00 AM PDT  "Minerality is difficult to fully explain," says Evan Goldstein, MS, president and chief education officer of Full Circle Wine Solutions. "There is no accepted definition of minerality in wine, no complete consensus on the characteristics that are associated with it, nor even whether it is perceived primarily as a smell, a taste or a mouthfeel sensation." Jancis Robinson, MW, calls the term "imprecise" and an "elusive wine characteristic" in The Oxford Companion to Wine. Words that are most associated with minerality are earthy terms like gunflint, wet stone, chalk and asphalt. Minerality is different than organic earthiness, says Goldstein, which he believes connotes something more alive and "filled with microfauna" like compost, potting soil, freshly turned earth or forest floor. So, what is minerality, and how does it get inside a wine? "That is the million-dollar question," says Goldstein. "We can really go through a rabbit hole here very quickly," says Federico Casassa, associate professor of enology at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo. "Linking minerality in wine is sexy and is a great sales pitch … However, to date, there is no clear scientific evidence connecting a specific terroir with the term. But we have some clues." Minerality is often associated with cool climates and stony terroirs. Casassa gives the classic example of Chablis, whose minerality is attributed to Kimmeridgian soils filled with marine sediment. "As it turns out, research has shown that, yes, there is some perceived minerality in Chablis wines," he says. "But this is more related to methanethiol, a volatile sulfur compound that kind of smells like shellfish.” Similarly, wines from Spain's Priorat appellation show minerality associated with the llicorella soils, lid to residual levels of malic acid. "This begs the question: Would blocking malolactic fermentation result in more 'mineral wines'?" asks Casassa. "Would having a comparatively low pH work in the same direction?" Quite possibly, he says. "A case could be made that soil composition can impact fermentation, which, in turn, can impact the production of volatile sulfur," says Casassa. "Another case can be made that soil pH and composition would impact juice/must and wine pH." People may use "stony mineral" descriptors to describe aromas and flavors, but it also relates to a wine’s texture. "A second important category is palate sensations, related to acidity and freshness, but also to gritty or chalky," says Goldstein. This is most commonly related to the structure of a wine's tannins: astringent, grippy, fine-grained or coarse. "In red wines, [minerality] is also found in cool climates," says Dr. Laura Catena, founder of the Catena Institute of Wine, and also managing director of Bodega Catena Zapata in Mendoza, Argentina. "We find it in extreme high-altitude Malbec from our Adrianna Vineyard at 5,000 feet [of] elevation, but not in the lower altitudes, where it's warmer." She says the same tends to be true of high-altitude Pinot Noir. "The aromas are a bit like flint, gunpowder or chalk," says Catena. "On the palate, one immediately feels the acidity, and there's a drying grip on the tongue, followed by the burning desire to eat something fatty." She's convinced that soil has an impact, possibly related to microbes and yeasts that vary according to altitude and soil type. "But [our researchers] are still in the process of studying this," she says. Regions associated with producing minerally wines include Champagne, Etna, Campania, Swartland and Priorat, among others. However you describe minerality, "it is beloved," says Goldstein. "For better, for worse, it's considered a sign of pedigree, when in reality, it's just…there." |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Wine Enthusiast. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

0 comments:

Post a Comment